I’ve been a bit inactive of late, a combination of getting a new machine learning computer and work. Still, it’s given me time have a rethink about my approach to generating new Grateful Dead audio.

I have two new approaches I want to try out this year. You could say one of them has already been done – that is, someone has already generated “fake Grateful Dead” audio, and you’ve listened to it and accepted it as the real thing for years!

Filling In The Gaps

Some older shows recorded on digital (typically early 80’s shows) can suffer from digi-noise, that is, pops and hiccups caused by the tape simply being a little old and losing some of it’s digital information. for a (really bad) example of this, see https://archive.org/details/gd1981-09-25.sbd.miller.88822.sbeok.flac16 (and check out the weird split Sugar Mag if you can get past the sound issues).

Not all tapes are this bad, and in fact in most cases when this happens someone like Charlie Miller will cover up the noise with some editing. But think about that sentence again: “cover up the noise with some editing”, hey that sounds like putting in fake audio. You have a piece of music with a discontinuity, and you have to fill it with something that sounds nicer and sounds like the GD, right?

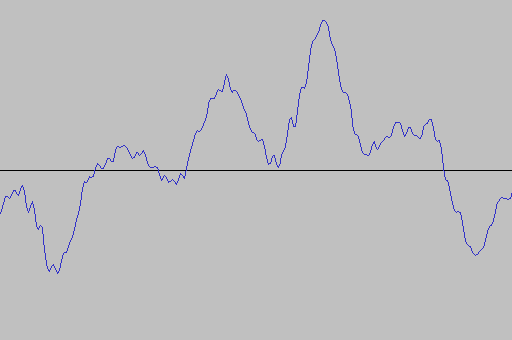

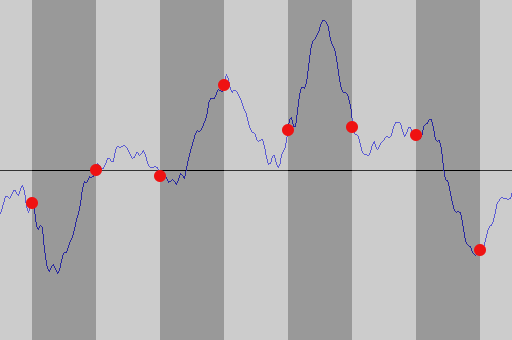

Well, almost. Look at a typical sample of digi-noise:

This digi-noise would be pretty loud compared with the rest of the audio (which is why we want to hide it). However, if we zoom in:

We can see that in fact the time for this audio event is from ~3.0195s to 3.0226, i.e. 0.0031s. That’s just 3/100’s of a second, which is probably easy enough to fix in a studio.

But this problem is ideal for generating new GD audio. Up to now, my effort has been to “teach” the computer by feeding it a large amount of GD, and then asking it to make some original audio. The problem with this approach is that the test is very difficult for the computer. If I first asked you to read every single Stephen King novel and then tasked you with writing a new paragraph in the same style, you would find that difficult. If however I asked you to start by filling in a missing word, well that would be a lot easier. Or if that was too much, start with a single letter.

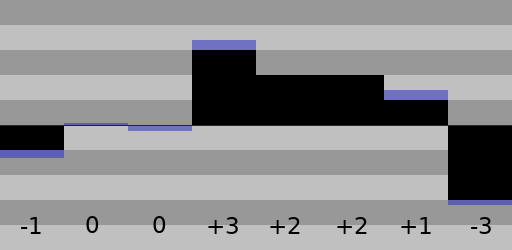

And that, in a nutshell, is the new approach. Instead of asking the computer to generate new audio from scratch, we instead ask it to fill in the missing audio. At first this will be someting like 3/100ths of a second. When that works, I simply ask it to fill it larger and larger gaps.

This approach has been tried for images, and the results are pretty good.

As you can see, the computer is able to generate many images to fill in the blank space.

Style Transfer

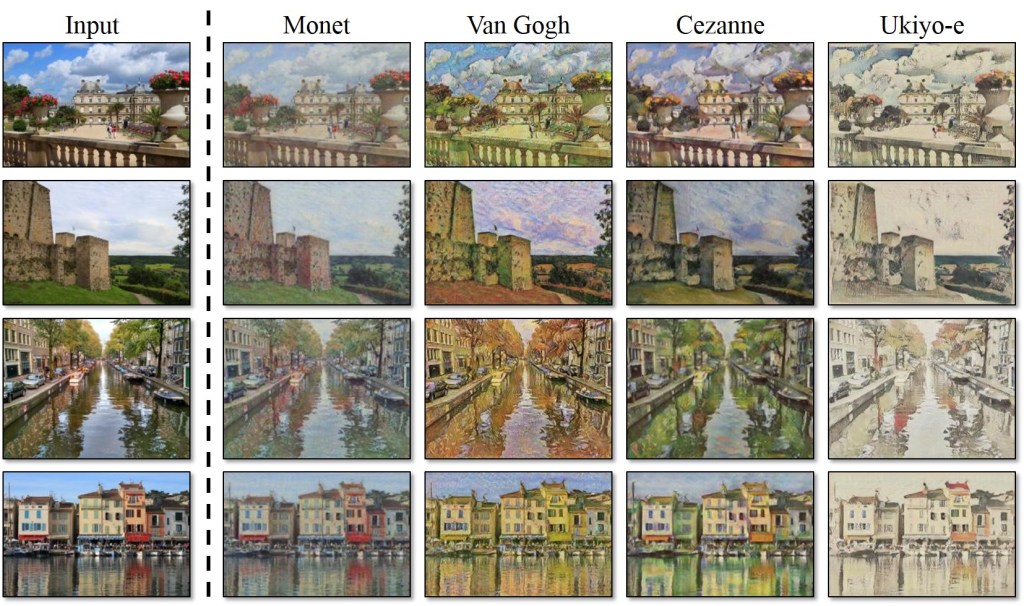

The second thing I shall try this year is a “style-transfer” with GD audio. These are best explained with images. Example: I have some photos. I also have digital copies of many paintings. I train the computer to recognise the style of the painter and “transfer” my image into the style of the painter.

So what styles are there in GD audio? Of all the tapes I have ever listened to, they are almost always one of two styles: audience or soundboard. So I will train the computer to tell the difference between them, and then ask it to output the audience audio into the style of a soundboard. I hasten to add that quite a few people prefer audience tapes (especially with the somewhat dry soundboard tapes of the early 80s), and that the style could easily go the other way.

Time Dependency

This last point is a technical issue, but one which could offer easily the best results.

So, a sound file is – to the computer – a linear series of numbers (each number being the volume at a given point in time).

What we are really asking the machine to do is to continue generating a series of new numbers based on the numbers so far.

But think how you might do this. To accurately guess what comes next, we work on a number of differing timescales. Note in the scale? Chord in the sequence? Verse to be sung? Is it a Bobby number next? All my attempts so far have been really concentrating on the “next note”, because music generates a lot of audio and so we only want to really check the local time area otherwise our computation gets really slow. In effect, to generate the next second of music, my code so far only looks at the previous 2-4 seconds. But to produce longer samples, we will need the computer to understand a lot more about the structure of the song.

I don’t want to get super-technical here, but Google researchers have a partial solution to this, which they used for creating realistic human voices (paper here: https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.03499).

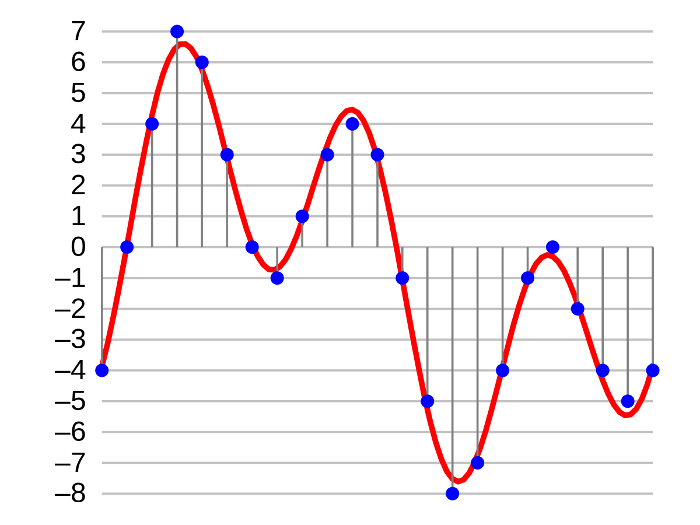

It essentially means my software will be able to take inferences from a much much larger area of the song. Generating a longer section of audio might not get any quicker but no longer will the computer have the memory of a goldfish. I’m really interested in this approach because it’s been tried and tested. Here, for example, is a section of music generated by a computer that has been trained on piano recitals.

My point being: If it can be done with piano recitals, it can be done with the Grateful Dead.